Russell Maze has spent the past 25 years behind bars. He was twice convicted of abusing and ultimately killing his infant son. But since the day in 1999 when little Alex stopped breathing and was rushed to the emergency room, Russell has maintained his innocence. A quarter century later, Nashville prosecutors finally agree with him.

After an exhaustive study of the case, Davidson County District Attorney’s Conviction Review Unit (CRU) has concluded that Russell Maze is innocent, and has asked the court to vacate his conviction. Alex’s mother, and Russell’s wife, Kaye Maze, pled guilty to reckless aggravated assault in hopes of regaining custody of baby Alex before his death. The CRU recommends that her conviction be vacated as well.

In a notice of intent filed in late December 2023, Nashville District Attorney Glenn Funk wrote, “This Office knows of clear and convincing evidence establishing Ms. Maze and Mr. Maze were both convicted of crimes they did not commit.”

Along with that letter, the CRU submitted a lengthy report detailing flaws in the conviction process and analysis from five medical experts who debunk the diagnosis of shaken baby syndrome, also known as abusive head trauma — citing new science that points to other likely explanations for Alex’s death. Last month, one of the detectives in the case filed a statement with the court saying that the police did not have a complete picture of Alex’s health and, as a result, erred in their investigation.

On March 26, a judge will hear the petition that could determine whether Russell Maze, who was 33 when he went to prison, will walk free after more than two decades behind bars.

An emergency, and immediate suspicion

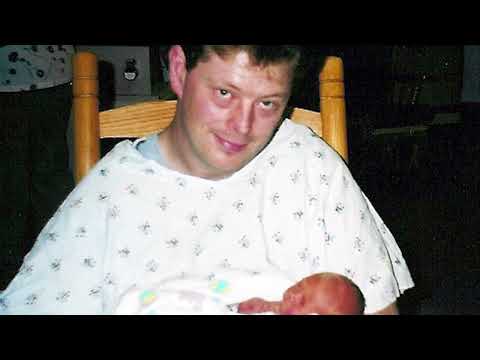

Around 3 p.m. on May 3, 1999, Kaye Maze went out to buy some formula and pick up some food for herself and her husband. Their son Alex, who had been born premature and was less than two months old at the time, had been fussy all day, thrown up more than once, and was running a fever. Russell stayed with him at their apartment on Welch Road in South Nashville while Kaye ran her errands. She returned about 40 minutes later to find an ambulance outside.

Alex had stopped breathing.

Both parents had taken infant CPR training, including a class for preemies, so Russell immediately started trying to revive Alex. When his initial attempts failed, he called 911. Paramedics arrived within minutes and were able to resuscitate Alex in the ambulance. By the time Kaye arrived — “hysterical when I saw it was my baby in trouble,” as she would later say — they were preparing to transport him to Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Distraught, Russell and Kaye rode to the hospital with MNPD detective Robert Anderson. This was the first time the new parents, anxious and separated from their ailing son, would find themselves in contact with law enforcement instead of health care professionals or other supports. But it would not be the last.

At VUMC, the attending physician in the Emergency Department, Dr. Ian D. Jones, was the first to examine Alex. He indicated the child was “unresponsive” and listed his condition as “critical.” Alex was intubated and, at least for the 30 minutes that he was examined, motionless. In his notes, Dr. Jones offered two possible diagnoses: sepsis; or “possible abdominal trauma or head trauma.” He ordered CT scans for baby Alex’s head and abdomen.

Soon after Alex was admitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, he was examined by Dr. Suzanne Starling, then-director of the Child Abuse and Neglect Program at VUMC. In her notes, she wrote that Alex had “multiple injuries” including: bruising on his face and abdomen; bleeding around the brain; severe cerebral swelling; areas of the brain that showed evidence of restricted blood flow consistent with stroke; and extensive bleeding behind both eyes.

“This constellation of injuries,” Dr. Starling wrote, “is seen in abusive head trauma.”

Dr. Starling also interviewed Kaye and Russell. In her notes, she wrote that the “parents give no history of injury that can account for the severity of these findings. … It is most likely to be related to an inflicted injury that involves a rotational force.”

In the “Plan” section of her referral form, Dr. Starling noted that the Davidson County Department of Children Services and Metro Police had both been informed of the situation and were on premises. Additionally, Russell and Kaye would be allowed supervised visitation for as long as Alex was in the PICU, but DCS should be notified of any transfer. “The parents,” Dr. Starling wrote, “are aware that an investigation must take place into the etiology of this injury.”

That investigation was actually already underway.

The Mazes did not know Dr. Starling was a child abuse specialist. And although they had already spoken with doctors, police and DCS officials by the time MNPD detectives Ron Carter and Kristen Vanderkooi questioned them each separately in a hospital conference room, they remained cooperative.

“We didn’t come here to bring you in to arrest you,” Det. Carter said near the beginning of his interview with Russell. “I’m just here to talk to you.” After establishing some basic facts — Alex’s birthdate, Russell’s place of employment — Det. Carter tried to get Russell to explain how Alex had sustained his injuries, which Dr. Starling had said could only come from violent shaking.

“I have never intentionally shaken my child to a physical, hurtful degree,” Russell insisted at one point. “If I have … shaken my child at all, it was an accident in picking him up.”

“That’s not how it happened,” Carter responded. “The injuries that your child has does not, did not come from picking up your child that way.” Carter then sought to remove intent from the equation. The only reasonable explanation, he said, was that someone walked in, saw Alex not breathing, picked him up and shook him.

Carter asked repeatedly if Russell could have shaken Alex, even accidentally.

Carter: “Think you may or could have? Think it’s possible?”

Russell: “Slight possibility, but I wouldn’t shake him. I would not shake him … for nothing, even if he was crying and he was turning colors I wouldn’t shake him to get him to stop.”

Over the course of this interview, Russell denied shaking Alex more than 10 times. But Carter kept pressing. During one stretch of questioning, most of Russell’s responses were recorded in the transcript as “[crying]” or “[inaudible, crying].” Det. Carter seemed to sense an opening. “Well it had to have happened some way, you know, shaking the baby like that,” he said. “That’s the only explanation.”

Carter then stopped asking whether Russell shook Alex, and instead asked how.

Carter: “Show me how hard you shook the child. Don’t … that … just wouldn’t do it. I’m gonna show you how.”

Russell: “It may be harder than that.”

Carter: “Yeah, it was harder. I’m gonna show you how hard that you had to shake the child. It’s like this. [shaking noise]

Russell: “No.”

Carter: “That’s the way it had to been … and if you were, you were excited and if you were upset and you thought that the child was not breathing, then you probably shook that child that hard if not more.”

Russell: “I guess I could. I just freaked. It’s possible.”

For Det. Carter, this amounted to a confession and a confirmation of Dr. Starling’s diagnosis. After Carter asked Russell whether Kaye could have shaken Alex, which Russell denied, they had this exchange:

Carter: “You probably done that or you did it?”

Russell: “What?”

Carter: “Shaking him?”

Russell: “It’s possible I did.”

Carter: “You did that. … I mean, you just got through telling me that you did … and the truth is that you did it.”

Russell: “Okay.”

Det. Carter then drove Russell back to the Mazes’ apartment, where police took photographs and collected evidence. In the coming days, he and Kaye would be at Alex’s side nearly around the clock. But they did not yet know that the decision to take him away from them had already been made.

Over the next year and a half, Kaye Maze would lose custody of her only child, who was released to a foster family in Bedford County. She would be told that DCS would never return Alex to her home with Russell there, and that her only option was to divorce him and admit he shook their son. She and her husband would be arrested and charged with child abuse. Thinking that making a deal was the only way to regain custody, she would plead guilty to assault. But she would never again be granted custody.

Six months after he first stopped breathing, Alex would be found unresponsive at daycare and end up in the hospital again. Then, in spite of her and Russell’s strong opposition, Alex would be taken off life support, and would die in her arms. Russell, who was not allowed to be with his son in those final moments, would stand trial and be convicted again, this time for first degree murder. He would be sentenced to life in prison plus 25 years, which he is still serving.

Shortly after Alex’s death, Kaye would write, “What the state of Tennessee has taken from us can never be replaced or forgiven.”

A complex medical history ignored

Even before his short life began, Alex Maze faced significant health challenges.

“I had an exceedingly difficult time carrying Alex from the very beginning,” Kaye wrote in 2000, in a detailed chronology of her son’s life. Her maternal age, 35, was considered advanced, and presented some potential risks. While pregnant, Kaye was hospitalized for two days for cramping and bleeding. Doctors at first thought she might have an ectopic pregnancy — a complication where the embryo implants somewhere outside the uterus — and she was given pamphlets on how to deal with a miscarriage.

The pregnancy was difficult enough that Kaye remained on bed rest for most of the duration and was unable to work. Doctors’ notes from this time contain references to bleeding near the gestational sac, blood clots and hemorrhage next to the sac. Kaye reported headaches, dizziness and vertigo. When she developed gestational diabetes, hypertension and low amniotic fluid, doctors decided to induce labor at 34 weeks — six weeks before Alex’s due date.

When he was born, Alex weighed a mere 3 pounds, 12 ounces. The umbilical cord had wrapped around his neck twice. And he spent nearly two weeks in the Special Care Nursery at Baptist Hospital, where at one point his heart rate jumped to 220 beats per minute as he slept. He was also diagnosed with hyperbilirubinemia (jaundice), which was treated with phototherapy, and hypospadias (a problem with the opening of the penis).

For his heart problems, Alex was referred to Dr. Frank Fish, a VUMC cardiologist who gave the Mazes a heart monitor. A few days later, Alex received a possible but unconfirmed diagnosis of supraventricular tachycardia — irregularly fast or erratic heartbeat. After a subsequent visit, Dr. Fish would write a letter to Alex’s pediatrician, Dr. Lesa Sutton-Davis, noting that Alex’s heart rate “varied considerably during exam, with fairly pronounced acceleration with even slight increase in activity.” Dr. Fish recommended a heart monitor study if symptoms persisted. Meanwhile, Alex continued to contend with a host of other health problems as well.

In one four-day period, Alex’s head measurement showed an increase of 4 centimeters. This unusual growth spurt seemed to go unnoticed by Dr. Sutton-Davis. Then, about a week after Dr. Fish’s preliminary tachycardia diagnosis, Alex came to see Dr. Sutton-Davis again because he was coughing and Kaye noticed that his bowel movements seemed “hard.” At a four-week checkup, Dr. Sutton-Davis again concluded Alex was doing well despite being below the fifth percentile for height, weight and head circumference. Her records included a reference to a normal head ultrasound, but no evidence of this scan has ever been discovered. And although Dr. Fish’s letter recommending a heart monitor study appeared in the file, there was no reference to it in Alex’s treatment plan.

In the three weeks after he left Baptist Hospital, Kaye and Russell took Alex to see health-care providers seven times, and got at least two phone consultations. At one visit, Kaye was told they were overreacting — “jumping at every little noise,” as she later recounted to detectives during questioning. But they were concerned. Once, she took Alex to a pediatric urgent care clinic because she felt he “wasn’t breathing right.”

None of this history was taken into consideration on the afternoon of May 3 — when Alex stopped breathing, was revived by paramedics and rushed to Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Dr. Jones, the attending physician in the emergency department who first examined Alex, incorrectly described him as “a full-term baby” with an “unremarkable” medical history. In fact, at this point, Alex hadn’t yet lived to see his original due date.

Dr. Starling, the child abuse specialist who examined him next, “obtained neither a prenatal history for Kaye nor a full medical history for Alex,” according to the CRU report. She also did not review pediatric records, and she would later testify in court, “This was a healthy child, by his parents [sic] report.”

Recalling the events of May 3, Kaye would later write that Dr. Starling “told me she thought Russell hurt Alex,” and that the baby “had injuries that you only see with shaken baby syndrome or being thrown through a car windshield.” There had been no car accident, so Dr. Starling’s assessment left only one option. According to Kaye, any time she or Russell tried to offer information about Alex’s previous medical problems, or had questions, Dr. Starling would repeat that “she was 100 percent sure that nothing could have happened to Alex except that someone had hurt him.”

That absolute certainty has had profound, life-altering consequences for the Mazes. But in the ’90s it was commonplace. Katherine H. Judson, executive director of the Center for Integrity in Forensic Sciences, told the Banner, “The conventional wisdom at the time was if you saw a child with a particular set of medical findings, the cause had to be shaking and could not have been anything else.” But according to the CRU’s investigation, Alex’s history of health problems suggests a number of possible explanations — all of which were either not properly investigated at the time or disregarded altogether because the presumption of abuse made it the only focus.

“Until now,” the CRU report reads, “this Court has never been presented with a complete and comprehensive analysis of Alex’s entire medical history and records.”

A hasty diagnosis, scrutinized with new science

In her examination notes on May 3, Dr. Starling, the child abuse specialist, pointed to a “constellation of injuries” that, as she noted, is “seen in abusive head trauma.” Sometimes referred to as the “triad,” those injuries are: bleeding around the brain; bleeding behind the eyes; and swelling of the brain. Even though Alex died more than a year later, that diagnosis carried over to the autopsy, in which Dr. Bruce Levy cited complications from shaken baby syndrome as the ultimate cause of death.

Based on present-day analysis from Dr. Darinka Mileusnic-Polchan, chief medical examiner for the Knox County Regional Forensics Center, the CRU investigation finds this postmortem diagnosis flawed and incomplete, calling it “a copy-and-paste exercise based on the initial clinical and imaging reports and not a thorough workup at the time of autopsy.” In other words, shaken baby syndrome appeared to be such a clear-cut reason that Dr. Levy did not bother to fully investigate — ignoring what the CRU report describes as “a constellation of intervening medical problems throughout that year.”

Dr. Mileusnic-Polchan is one of five medical experts, whose specialities range from pediatric medicine to forensic pathology, formally consulted by the CRU. Another of those experts, neuroradiologist Dr. Lawrence Hutchins, concluded that “trauma is so unlikely it should not be a consideration.”

Not only did the experts agree that trauma was not the cause of the injuries Alex presented with on May 3, they also described a number of other possibilities based on their analyses of the records.

According to experts cited in the CRU report, there is a distinct possibility that Alex had some kind of undiagnosed metabolic disorder. Alex’s macrocephaly, or large head size relative to the rest of his body, can be associated with Glutaric Acidemia Type 1 (GA1). There was no screening for GA1 in 1999 as there is today. Metabolic disorders can also mimic sepsis — one of the original diagnoses under consideration when Alex was first examined in the emergency department at VUMC.

Still, the possibility of a metabolic disorder was never explored. “Despite the fact that Dr. Starling’s own CARE consult template form included sections for lab results of plasma amino acids and urine organic acids,” the CRU report notes, she left them blank; these are “key elements of metabolic disease evaluations.” Additionally, the transcranial bleeding Alex experienced could have been caused by stretching of intracranial veins, a condition associated with GA1.

“Since the time of this trial,” the CRU report reads, “scientific understanding of what causes bleeding around the brain and its prevalence in premature infants has greatly expanded.”

Alex underwent another CT scan on May 6 — three days after he was first hospitalized — that showed increased intracranial hemorrhage. Continued bleeding is consistent with other conditions besides trauma.

Another of those “classic shaken baby syndrome” indications, bleeding behind the eyes, was similarly not as straightforward as it was presented to the court. At trial, Dr. Starling testified that other than abusive head trauma, “there’s really nothing else that causes all three layers in the entire back of the retina to be obscured by all this blood.”

One of the CRU’s consulting experts, Dr. Franco Recchia, disagreed with this: “Published medical literature, including articles that did not exist at the time of trial, and my clinical experience have shown that conditions other than trauma can be associated with this clinical appearance.” He also described Dr. Starling’s testimony as “inaccurate and misleading,” and offered a list of other possible causes, including: infection; “anatomic malformation of blood vessels in the brain”; “disorders of amino acid metabolism” such as Menkes syndrome; and blood disease.

Two months after his initial hospitalization, another scan showed numerous retinal hemorrhages. This kind of continued bleeding is also not consistent with a traumatic injury.

On top of that, Alex’s retinal hemorrhages were considered by the ophthalmology consultation to be consistent with shaken baby syndrome, but with one important caveat: “assuming his bloodwork was normal.” It was not. In fact, Dr. Michael Laposata reported that Alex’s red blood cells were low in number and abnormal in size and shape. But this blood work was not completed until days after Dr. Starling made her diagnosis.

According to CRU consulting expert Dr. Lawrence Hutchins: “brain scans show a pattern of bleeding characteristic of arterial strokes, not trauma.” In fact, after an MRI in 1999, Dr. Frederick Barr at VUMC diagnosed Alex as having strokes. And Dr. Starling’s own notes indicated “areas of low attenuation in the brain that are consistent with infarct” — in other words, places on the head scan that showed signs of blood restriction that is commonly associated with stroke. But Dr. Starling attributed the strokes to abusive head trauma.

In examining the medical records for the case, the experts did not find enough evidence to determine a cause for Alex’s death conclusively. Even so, the report makes this much clear: “What every single expert the CRU consulted with agrees upon is that Alex Maze did not die from abuse.”

A flawed investigation

In addition to the presumption of guilt that was cast on them as soon as Dr. Starling made the diagnosis of shaken baby syndrome, there is the fact that neither Kaye nor Russell had an attorney present with them when they were questioned separately at VUMC. Furthermore, the CRU report states, “scientific understanding of trauma has changed tremendously in the last ten years.” Effects can include “difficulty concentrating, distortion of time and space, or memory problems.” With their son’s life hanging in the balance, the Mazes were undoubtedly experiencing trauma the night they were questioned repeatedly and with increasing suspicion.

Because detectives had been told that abuse was the only possible cause of Alex’s injuries, and therefore assumed either Russell or Kaye were the culprits, they questioned the parents as if there were scientifically no doubt about what had happened. This tactic is known as “the false forensic ploy.” As Judson with the Center for Integrity in Forensic Sciences explained, “When someone is told all the scientific evidence shows that you did it, what the studies show is that you’re more likely to get a false confession under those circumstances.”

Now, even one of the officers involved in the investigation is saying that’s what happened.

In an extraordinary move, Vanderkooi, now a former MNPD detective, submitted a sworn affidavit to the court on Jan. 30. “Dr. Starling’s diagnosis framed our investigation and left no other possibilities,” the affidavit reads. “If other medical possibilities had been acknowledged by Dr. Starling, the police investigation would have been broader.” Taking those possibilities into consideration now, Vanderkooi says, “it is clear Russell Maze’s statements were not a confession to any action causing injury to his son.”

But at trial, Russell literally had no defense against the medical claims being lodged against him. His legal counsel did not consult with a qualified medical expert.

In the years since Russell Maze’s conviction, new scientific understandings like the ones described in the CRU report, written by CRU Director Sunny Eaton and Assistant District Attorney Anna Benson-Hamilton, have cast doubt on many shaken baby syndrome cases. Nationally, there have been at least 34 exonerations. Judson said this is an undercount because not only do many people elect not to undergo a new trial, others plead guilty, or have their cases dismissed for reasons that do not fit the strict criteria of the national registry.

Russell has always maintained his innocence. He appealed his conviction in 2006 and was denied. He then filed for post-conviction relief in 2007, arguing that his legal representation had been ineffective, in large part due to failure to consult medical experts. Finally, on June 9, 2008, Dr. Patrick Barnes and Dr. Edward Yazbak testified that, in their opinion, Alex Maze’s death was not caused by an injurious act. But the court was not moved, and upheld Russell’s conviction.

His legal options exhausted, Russell has remained in prison. He and Kaye are still married.

“Nothing will ever give us back our son,” Kaye wrote shortly after Alex’s death in 2000, “but getting Russell out of prison for something he did not do would help the healing process begin.”